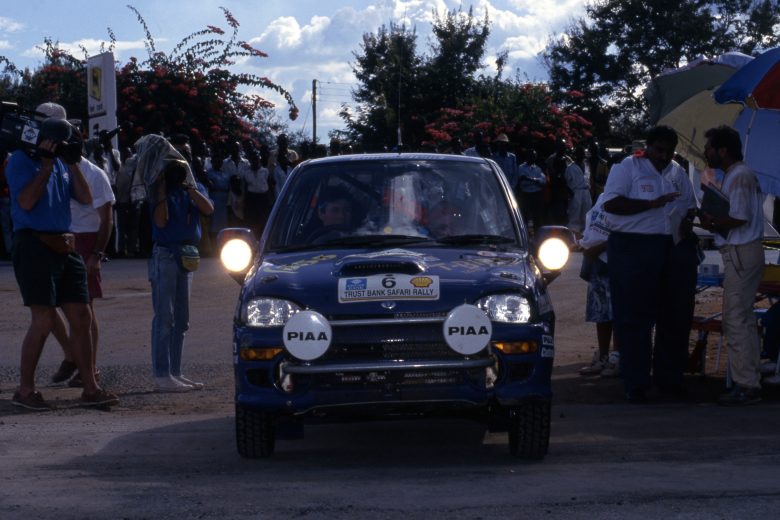

Did Colin McRae want to do the Safari Rally? Absolutely. Did he want to do it in a Subaru Vivio Sedan 4WD? According to Prodrive, yes, he did.

It was 1993, McRae had just secured his second consecutive podium at the Swedish Rally, and he was ready to take on the world. But a supercharged 660cc Japanese Kei car wasn’t exactly in his plans. Until it was.

The 24-year-old Scottish driver was eager to see Africa, and Subaru Tecnica International’s founder, Noriyuki Koseki, was keen to get the Vivio some attention. So, they made it happen.

Few predicted the 555-liveried Subaru would even survive the first section of the event. McRae’s co-driver, Derek Ringer, might have been among the skeptics.

Ringer recalls, “We went there without any real understanding of what we were letting ourselves in for. The problems started before the event even began.”

This was their first time at the Safari Rally, and the duo was new to creating the more detailed, descriptive pacenotes required for the 1300 competitive miles that lay ahead.

“We tried to do a recce in a Nissan pickup truck,” said Ringer. “Pretty quickly, we realized we didn’t know how to make proper pacenotes for Africa, and neither the Nissan nor the Vivio was going to make it through the entire route.”

In the end, they only recce’d the first two days of the five-day rally and borrowed notes from their teammate for the rest, just in case they got that far.

“Two days before the rally started, we tested the car on one of Kenya’s smoothest gravel roads, and after driving just 30 kilometers, the car stopped. The sun was setting, I had a lot of cash in my rally bag, and all the locals had gathered to see what this strange little car was all about. I was starting to feel uneasy,” Ringer explained.

“Eventually, four locals showed up in a battered old car, and we convinced them to tow us out. They said they had no petrol, so I offered to fill their car if they managed to tow us to the main road. We got about 300 yards before their car gave up in a cloud of steam.”

With the recce sort of done, it was time for the rally. The Scotsmen quickly caught attention on the rough roads southeast of Nairobi.

“We were up to fourth place after the first couple of sections,” said Ringer, “but there was no way that would last. Near the end of the fifth section, the front suspension broke completely going into a river crossing.”

“After crossing the river, the rear differential broke. Koseki’s mechanics weren’t experienced rally mechanics; they were the winners of a competition for Subaru’s best mechanics from their dealer network in Japan – their prize was to work on the Safari Rally. They didn’t have a clue what they were doing. Colin and I stood there, bewildered, watching as they tried to fix the Vivio. We were astonished when they actually got it working again.”

“Things were going well for a while until the car completely broke down two sections later near Mombasa. After that, we headed to the hotel swimming pool for four days.”

When McRae spoke to British journalist David Williams in Mombasa after his retirement from the rally, he glanced at the hotel’s pool and deadpanned, “I can’t think of a better place to retire.”

The adventure had ended. It lasted longer than most had expected, but it wouldn’t be repeated.

Four years later, McRae returned in a more capable Subaru, this time in a proper four-wheel drive, and went on to win the event by seven minutes.